http://www.machinerylubrication.com/Read/29121/complex-hydraulic-problems

In 1935 the U.S. Army Air Corps held a “fly-off” between two aircraft vying to win the contract for the military’s next long-range bomber. The competition was regarded as a mere formality because Boeing’s Model 299 was the logical choice. It could carry five times as many bombs as the army had specified and fly faster with twice the range of previous bombers.

In 1935 the U.S. Army Air Corps held a “fly-off” between two aircraft vying to win the contract for the military’s next long-range bomber. The competition was regarded as a mere formality because Boeing’s Model 299 was the logical choice. It could carry five times as many bombs as the army had specified and fly faster with twice the range of previous bombers.At the allotted place and time, a small crowd of army brass and manufacturer representatives watched as the Model 299 test plane taxied onto the runway. The airplane took off effortlessly and climbed steeply to 300 feet. The small group of spectators watched in horror as the plane suddenly stalled and dropped out of the sky. The Model 299 test plane exploded in a fireball when it smashed into the ground, killing two of the five crew members, including the pilot.

The subsequent investigation revealed there was no mechanical fault with the aircraft. The crash had been caused by pilot error. The Model 299 was significantly more complex than any previous aircraft. This new plane required the pilot to manage four engines, each with its own air-fuel mix, retractable landing gear, wing flaps, electric trim tabs, variable-pitch propellers and many other bells and whistles. While doing all this, the test pilot had forgotten to release a mechanism that locked the elevator and rudder controls.

| 80% | of machinerylubrication.com visitors use checklists for maintenance work at their plant. |

As a result, the Boeing aircraft was deemed “too much airplane for one man to fly.” The army declared Douglas’ competing design the winner, and Boeing nearly went bankrupt.

The story doesn’t end there, but first let me explain my reason for recounting it here and why it has relevance to all of us today - nearly 80 years after the event. It’s a story about coping with complexity and a graphic illustration of how technological advancement and the complexity it often creates brings with it what Atul Gawande describes in his book, The Checklist Manifesto, as “entirely new ways to fail.”

Believe it or not, complexity is a science all on its own. In Gawande’s book, he references the work of two professors in this field, Brenda Zimmerman of York University and Sholom Glouberman of the University of Toronto, who have come up with a three-tier classification system for the different kinds of problems we face in the world: simple, complicated and complex.

Simple problems, they suggest, are like baking a cake. There’s a recipe and sometimes a few basic techniques to learn, but once these are mastered, following the recipe results in a high probability of success.

The Power of Checklists

“Under conditions of complexity, our brains are not enough,” said Atul Gawande during a recent lecture series. “We will fail. Knowledge has exceeded our capabilities. But with groups of people who can work together and take advantage of multiple brains preparing and being disciplined, we can do great and ambitious things. As we turn to something like a checklist, what we see is something that is lowly, humble, overlooked and I think misunderstood. But when we pay attention to where our weaknesses are and then pay attention to how something like a checklist works to supplement the failings of our brains and the difficulties teams have in making things come together, what you realize is that an idea like this can be transformative.”Complicated problems are like sending a spaceship to the moon. There is no straightforward recipe. Unanticipated setbacks go with the territory. Coordination and timing are critical to success. However, once you’ve figured out how to send one rocket to the moon, the process can be repeated and perfected.

Complex problems are like raising a child. Every child is unique. While raising one child provides experience, it doesn’t guarantee success in raising another. In these situations, expertise is valuable but not necessarily sufficient. The outcomes of complex problems are also highly uncertain.

This hierarchy of problems has merit, but it’s telling that the people who came up with it are professors of complexity and not simplicity. I have an alternative problem-classification system that will never make it into any academic journal but that has practical application all the same. It involves obvious and invisible problems.

Obvious problems are the ones we can or should see and address but happily ignore while we get consumed trying to find invisible ones. For instance, global warming is still in many respects an invisible problem. On the other hand, thousands of coal furnaces billowing smoke into the atmosphere all over the world are an obvious problem. If the focus was on fixing the obvious problem (global pollution and smog), the long-running argument about the invisible problem (global warming) may not even be necessary.

Both of these problem-classification systems have application. For example, according to the professors’ definition, troubleshooting is a complex problem. Success in one troubleshooting assignment doesn’t guarantee success in another. Experience is valuable but not necessarily sufficient. In addition, the outcome is often uncertain.

This doesn’t mean the cause of the problem is always invisible. Often it’s not. A problem can be complex in appearance, but its causation (and solution) can be quite obvious. This is why the troubleshooting process should always begin with the checking and elimination of all the easy and obvious things first. Resist the temptation to go looking for the invisible unless or until you have to.

These days, increasing complexity combined with an overwhelming amount of work and a severely limited amount of time often mean the only way to survive is by addressing the biggest problems to their shallowest depth. This is a frustrating, futile and sometimes deadly position to be in.

It was no different back in 1935. Despite the Model 299 being declared “too much airplane for one man to fly,” a few army insiders were convinced it was flyable. So several aircraft were purchased as test planes, and a group of army test pilots got together to figure out what to do. They concluded that flying this new plane was too complicated to be left to the memory of any one man, regardless of how well he was trained. So they created the very first pilot’s checklist.

The result, as outlined in Gawande’s book, was that the Model 299 went on to fly 1.8 million miles without a single accident. The army ended up ordering 13,000 units of what became the B-17 bomber, an aircraft that gave the United States a decisive air advantage during World War II.

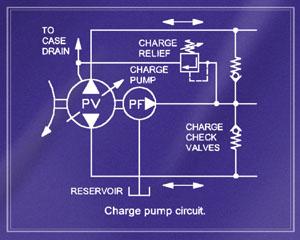

This outcome is a great advertisement for the value of checklists as a tool for coping with complexity (and the perils of relying on memory). The use of checklists is something I’ve long regarded as having practical application in hydraulics. In Insider Secrets to Hydraulics, I expound the benefits of developing and using a pre-start checklist to prevent “infant mortality.” In Machinery Lubrication, the idea of an equipment pre-purchase checklist has been advanced and discussed in some detail. More recently, I’ve developed a process and accompanying checklist for effective troubleshooting. These examples are by no means exhaustive.

Clearly the pace of technological advancement shows no signs of slackening. If anything, it’s accelerating. This means maintenance professionals of the 21st century not only must be competent problem-solvers, but they also must be able to wrestle with complexity and win. Checklists can be a big help. Modern-day pilots are trained to rely on them. Why shouldn’t we?

About the Author

As I’ve gotten older, I have tried to curtail my consumption of fast food. I’m aware that the fat content, calorie counts and general nutrition levels are not the healthiest available. I know that as we age, we should watch our cholesterol, our weight and make sure that we eat healthy. I also know that my diet will directly contribute to the length and quality of my life. With all that being said, I love fast food. I am usually pretty good at keeping a balance of healthy eating and not-so-healthy eating, but sometimes I just want something that comes quickly and cheaply even though it may not be the best thing for me.

As I’ve gotten older, I have tried to curtail my consumption of fast food. I’m aware that the fat content, calorie counts and general nutrition levels are not the healthiest available. I know that as we age, we should watch our cholesterol, our weight and make sure that we eat healthy. I also know that my diet will directly contribute to the length and quality of my life. With all that being said, I love fast food. I am usually pretty good at keeping a balance of healthy eating and not-so-healthy eating, but sometimes I just want something that comes quickly and cheaply even though it may not be the best thing for me.

As an unrepentant checklist fanatic/junkie, I recently had to pick myself up off the floor in an airport newsstand. There with all the romance novels and the latest silver-bullet management books was The Checklist Manifesto by Dr. Atul Gawande. A best-selling book about checklists? The world wants to read about checklists?

As an unrepentant checklist fanatic/junkie, I recently had to pick myself up off the floor in an airport newsstand. There with all the romance novels and the latest silver-bullet management books was The Checklist Manifesto by Dr. Atul Gawande. A best-selling book about checklists? The world wants to read about checklists?